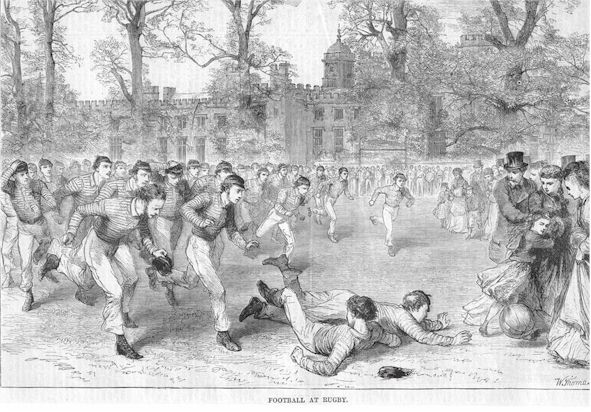

It is a fact sometimes commented upon in histories of British state theory that two of the key thinkers, Henry Sidgwick and Thomas Hill Green, were schoolmates. Recalling his time at Rugby in the 1850s, TH Green remembers Sidgwick, who grew into the philosopher behind Rule Utilitarianism, as the ‘chubby pot-bellied little Rugby boy.’ Both were students at the school styled by headmaster Thomas Arnold, an influential reformer who implemented his vision of the public school as an institution built to spread good character amongst the youth. He wanted to make Rugby students into gentlemen, and had two central ideas for how to do it – sports, and prefects – which he believed would lead to a respect for rules, fair play and discipline. His example formed the model for Victorian public school education.

The heightened emphasis on the formation of children’s moral character had begun in the 1820’s; with the Clarendon Commission of 1864, the importance of principles and morality in education – and the role of sport in building them – had became formally recognised. Indeed, TH Green’s early work on the Schools Inquiry Commission of 1866 reveals his interest in this area. This was the Victorian century, and everyone was obsessed with morality. But the role of schools was only one element of a wider question that 19th century theorists touched on: where does the moral character of individuals come from, and how should the state fit in?

JS Mill’s ‘On Liberty’ (1859) set the standard for liberal answers to this question. It is not for the state to intervene on moral terms, or to try to form the morality of its citizens. Rather, the state’s role is limited to two principles; utility, and harm, the former requiring the state to maximise happiness amongst its people, and the latter forbidding state intervention except when actual harm is being caused to an individual.

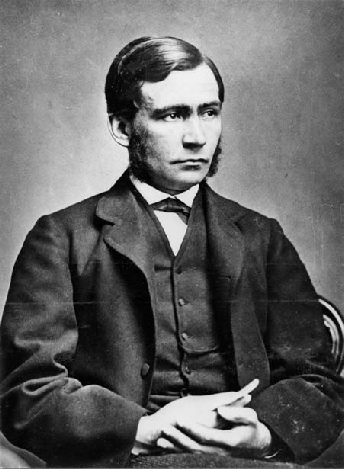

Like Mill, Green was keen to say that the state should have no role in the morality of the individual. His Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation (1880) and Lectures on Liberal Legislation (1881) argued that the coercive nature of law cannot force individuals to be moral, as it only governs outward acts rather than the internal motivations that guide them. He suggested that statist paternalism fails because it puts coercive force behind the sorts of acts which individuals should do out of their own moral character, such as helping the poor, through higher rates of taxation rather than charitable acts.

He clarified his ideas of where the state should fit in by distinguishing conventional morality from higher morality. Conventional morality is the morality of following the law, abiding by the legal obligations the state imposes. It is conventional because it is basic – a baseline level for individuals to reach. However, by enforcing this baseline, the state thus creates the conditions of security which provide the foundation for the emergence of a higher moral standard, the ‘ideals of goodness’ that blended Victorian and Christian influences. This standard is up to the individuals to pursue themselves, freely, out of their own choice.

In this way, the state is a sort of ‘enabler’ for individuals. It enables individuals to be the best version of themselves that they can be. For Green, this role for the state included the removal of barriers, such as poverty, to the individual’s capacity to freely exercise their rights. Though everyone may share the right to buy a house, provide for their family, or pay for their medical care, the state’s traditional, laissez-faire role in providing for this right was in removing legal barriers. Green thought it should go further. These rights mean little, he thought, without the individual also possessing some form of ‘power’ to fulfil their right, which in practice means having the money to afford it. A factory worker and his boss may have the same rights, but they don’t really. The worker is far less free, in the real world, to do as he pleases. This reflects Isaiah Berlin’s distinction between positive and negative liberty – negative liberty is the lack of barriers preventing an action, whilst positive liberty is the existence of actual conditions that makes it possible. TH Green’s incorporation of the former led to the tag of ‘modern liberalism,’ rather than the more negative, classical liberalism that went before.

The modernness of this thought is in the way it rethinks what freedom for an individual means. It is not only freedom from infringement, but also the power to go out and in pursuit of your interests under the framework of the state. And the link to another idealist, Bosanquet, is in how Green puts the individual right at the centre of his analysis. The state is valuable insofar as it provides meaning, freedom and value for individuals.

_____

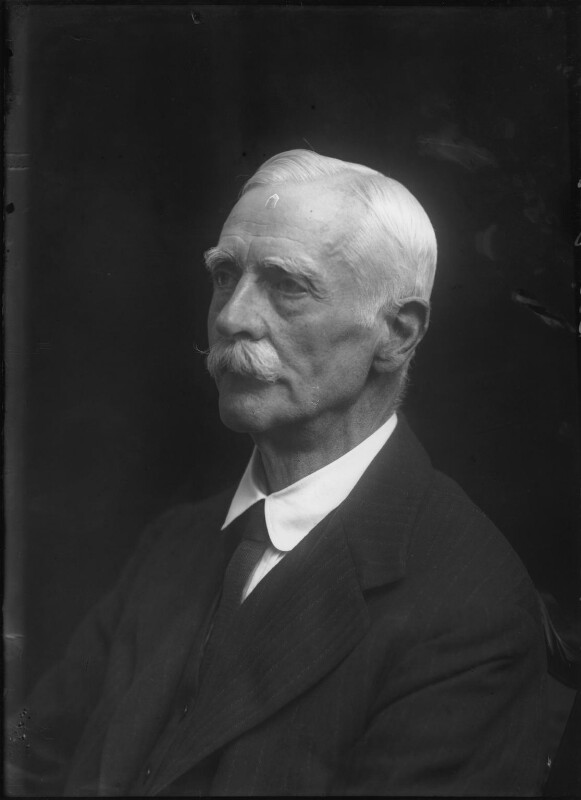

Bernard Bosanquet’s idealism

Bernard Bosanquet, writing in the idealist tradition a little later, was in some ways similar. He had a similarly evangelical view of his own role in promoting moral character. He became involved in many charitable activities, as Green had been involved in the School Inquiry Commission, out of a sense of conviction. He is also someone who fits into the story in which Mill’s ‘On Liberty’ is an episode. In fact, part of Bosanquet’s motivation was his belief that Mill had not gone far enough; his defence of individuals against the state was not strong enough. As he showed, when the utility principle and harm principle come together, we get some striking problems with where the authority of the state should lie. Preventing poor parents from having children could, with Mill’s principles, be in the state’s remit.

Bosanquet’s ‘philosophical’ theory of the state (1899) therefore went far beyond Green’s limited conception of the state as a framework for individuals to pursue higher morality. He was motivated, partly in the Hegelian tradition, by a desire to show how the state’s functions ‘flow from individual nature,’ and so engaged in a significant philosophical project, demonstrating the interdependence between individuals and the state or society (which he tended not to distinguish). Aiming to go beyond Green, who he described as too cautious, Bosanquet drew from abstract psychological thought such as that of William James in order to analogise the individual mind as a ‘vast tissue of systems’ in which each perceive a different part of the ‘social whole.’ In the same way, society too is a set of overlapping systems of relations between individuals and groups, all fitting together in the ‘unifying’ idea of the state. Just as different systems in the mind worked together organically, different groups in society fit together with their destiny being to be ‘gathered up’ in the state, our widest common experience. In this philosophical vision, the individual finds meaning in the opposite way to the laissez-faire vision – not by being left alone to pursue goals, but by participating in the ‘inviolable unity’ of the state. His idealism was about this kind of holistic, all-fitting-together, interdependent concept of the state.

‘The true social group is not formed by the recognition of similarities, but by the integration of differences. Integration rather than compromise, to include what all have to offer in a complete conception of the collective will… The aim of politics is to find and realise the individual, who is still the social unit, but this time as a member of a group, determined by his relations.’

Introduction to The Philosophical Theory of the State, 1899

His definition of a ‘philosophical theory’ of the state gives clues to his thought. He describes it as the study of the state as a whole and for its own sake, its total, unbroken fullness. The human mind can only achieve its full proper life in a community of minds, or more strictly, in a community pervaded by a single mind, the collective mind, uttering itself consistently though differently in the life and action of every member of the community. Every type of person in the community has a certain distinctive type of mind, fulfilling its own specific function within the collective, and fitting into the whole as organs fit into the body.

So what exactly is the state, then? It is simply society as a unit, exercising control over its members by absolute physical power. Its goal is the same as society’s goal, as individuals’ goals: to create the best life for individuals. The end of the state is in enabling people to have recourse to rights claims, facilitated by the state removing hindrances to them – this is the same positive liberty idea as TH Green. It is a grand, philosophical way of tying everything together, then bringing it all back to the purpose of furthering the interests of individuals.

______

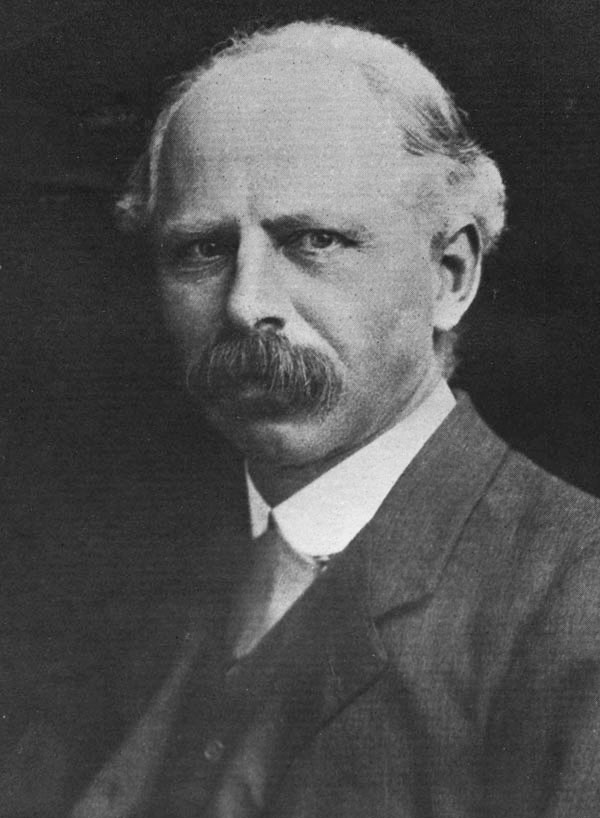

Hobhouse’s successful critique of the idealists

Whereas TH Green provided a limited vision of the state and the individual as fitting together, Bosanquet’s thought was far more abstract. The persuasive and passionate criticisms made by Hobhouse in 1919 encapsulate the gap between reality and the idea of the state Bosanquet presents. One pervading criticism throughout Hobhouse’s work is that by failing to distinguish the actual state from his vision of the ideal state, Bosanquet misses the distinction between writing about what ‘is’ and about what ‘ought’ to be. Bosanquet’s description of the state as that which ‘maintains the external conditions’ of the good life, for instance, does not account for those states in the real world which may not do this. Is the state only a ‘state’ to the extent that it maintains these conditions? Or to give my own example, Bosanquet states that ‘all groups are organs of this single pervading life’ in Ch.7, yet very often groups are set up in direct opposition to the life of the state and society – for instance today, a rise in ‘abolitionist’ groups rejecting the existence of the police as well as anarcho-syndicalist groups are visible in the US and the UK. Yet organically, there is not an organ which is set up with the aim of destroying the life of the being within which it exists. Indeed, Bosanquet’s 1919 preface to his 1899 work shows that he noticed this contestation in some way – he saw the ‘growth of syndicalism everywhere’ and proclaimed that the state is dead.

A second powerful and related criticism made by Hobhouse is that Bosanquet misunderstands the experience of the individual within the state because of his philosophical approach. As Hobhouse rightly suggests, the interests of individuals can conflict with the shared interests of the totality, yet under Bosanquet’s framing, individual interest is only maximised when participating in the collective. Whereas Bosanquet speaks of a ‘will’ which is general and shared by all, the reality is of course different – there are many wills in society, perhaps as many as there are individual people. Furthermore, these ‘wills’ are themselves fragmented and complex, and there is not a ‘real will’ within each individual, but an aggregate of different interests and desires, constantly in flux. Connecting this to the state, Hobhouse persuasively argues that this diversity means that we do not all experience the ‘social totality’ in the same way. Though we may all share the act of experiencing the state together, our actual individual experiences are distinct and unique – individuality is not participating as a part within a system, but rather the core of personal experience that we each have in the world, isolated within our own physical body – the ‘individuated’ experience. This disagreement over individual experience matters to whether Bosanquet saw a ‘real’ or an ‘ideal’ state because, for him, the individual and state were models of each other, both parts of the same whole. Yet by failing to separate out individual from state, character from environment as Hobhouse did, Bosanquet reveals an overly philosophical emphasis.

Ultimately, the idealist attempt to tie the state to society to the individual in one neat knot was too far removed from the complex realities of politics to last. By the 1930s, pre-WW1 thought looked outdated, and bolshevism reanimated the idea of the state on the progressive side. Idealism was left in its place, at the turn of the century, as an influential idea that did not last.