*This essay connects classical ideas about rhetoric to the 21st century scene of tv chat shows, twitter, news by phone and laptop etc. It shows why rhetoric has changed, how it has changed, and the problems connected with rhetoric today. Specifically – that it makes political leadership harder*

Introduction

In 4th century BC Athens, Aristotle wrote Rhetoric, his canonic treatise on public speaking which still influences rhetorical studies today, defining the art of rhetoric as the ability to recognise and use the available means of persuasion through public speech in a particular situation (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1992: I.2). Modern scholars have further emphasised the importance of the context in which political rhetoric is delivered, arguing that greater attention must be paid to the different elements that form this context (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1958, Bitzer 1968). This essay explores the relationship between political rhetoric and leadership by focusing on 21st century Britain, examining more specifically the contexts in which contemporary political rhetoric is delivered.

This essay begins by examining some classical antecedents to modern rhetorical studies, arguing that a focus on the context of rhetorical performances is not new but has been central to rhetorical studies throughout its history. I then explore the contexts in which political rhetoric is delivered in 21st century Britain, making comparisons with the 1945 general election in order to demonstrate that political rhetoric today takes place within new and structurally distinct contexts. I draw from social theories of leadership to argue that political leaders in democracies are expected to demonstrate their suitability to lead by presenting themselves as someone who reflects and embodies widely held values and beliefs throughout the polis. I connect this to political rhetoric by demonstrating that the contexts in which political rhetoric was traditionally delivered in Britain, such as in 1945, provided an important opportunity for political leaders to construct this identity. I argue that, because these contexts have changed since, political leaders have been forced to develop new rhetorical styles and techniques for communicating with 21st century audiences. However, these new rhetorical styles are poorly suited to political leadership and the construction of a leader’s identity, as I will show.

____

Understanding political rhetoric within its context

Historically, manuals of rhetoric emerged in Greek antiquity, in conjunction with reflections on the nature of democratic argumentation. Aristotle’s Rhetoric anointed Corax of Syracuse who, after an uprising established Sicilian democracy in 465 BC, wrote the Art of Rhetoric to instruct citizens in how they should argue in Greek courts, as its inventor (Kennedy 1994). In the intervening years from Corax to Aristotle, rhetorical techniques came to be professionally taught in Athens by the so-called Sophists. Plato’s Sophist, a dialogue written in 360 BC, somewhat damaged their reputation by contrasting the ‘duplicitous’ Sophists with the ‘virtuous’ philosopher, but a training session in Greece was a near-obligatory rite of passage for aspiring politicians including Cicero for several centuries to come (Foss 2014).

Aristotle as well as the Sophists agreed that politics is an arena of, to appropriate W.B. Gallie’s term, ‘essentially contested questions,’ where no absolute ‘truth’ can be agreed upon. Adversarial rhetorical argument is consequently required to settle democratic disputes and establish a collective position which is not based on indisputable truths but, as Corax already argued, on probable conclusions (Gallie 1955). Aristotle thus recognised that the polis (i.e, the Ancient Greek city-state) exists in a state of inevitable contestation between groups with particular interests caused by social plurality (see Finlayson 2007). Where these interests are to an extent irreconcilable, persuading and convincing others of one’s perspective becomes all the more crucial. When Aristotle described man (sic) as a ‘political animal,’ he thus echoed the contemporary rhetorician Isocrates’s claim that the ‘instinct to persuade, to make clear to each other whatever we wish’ is the core of politics, and is enabled by the participative culture of democracy (Isocrates, Nicocles 3.6).

If persuasion rather than proof is called for, rhetoric must appeal specifically to those it aims to persuade – the audience. To do so, Aristotle argued that orators should not only employ logic (logos) but also establish their credibility as a speaker (ethos) and play on the audiences’ emotions (pathos). When using these techniques, orators must recognize and respond to the strands that unify their particular audience, the common cultural values, ways of thinking and emotive tendencies that thread through the collective – which Aristotle termed endoxa (Most 2015).

In the mid-20th century, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca influentially refocused rhetorical studies even further on the audience. Highlighting the flexible nature of rhetoric, they proposed a distinction between ‘argumentation’, which builds on premises accepted by the audience to move towards reasonable conclusions, and ‘demonstration’, which claims to reveal axiomatic truths (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1958). In Aristotelian terms, rhetoric is thus as much about the particular context and audience as it is about the means of persuasion.

Further contributing to this growing focus on audience and context, Lloyd Bitzer’s The Rhetorical Situation (1968) argued that just as questions call forth their answer, the context within which rhetoric is delivered calls forth rhetorical responses and grounds rhetorical activity. By locating the audience within the broader context, or ‘rhetorical situation’, Bitzer provides a framework for understanding how orators adjust rhetorical performances to different situational constraints. Referencing the dialogue of Trobriandian fishermen on an expedition, who describe water depth and shout verbal instructions to each other as guides to physical action, such as when to drop or lift the net, Bitzer suggests rhetoric is a pragmatic response to external events every bit as functional as those physical actions themselves. The ‘urgent situation’ that demands rhetorical response is the exigence – the first element of the rhetorical situation. The audience, those influenced by rhetoric to perform the actions it calls for, is the second element, whereas the constraints of the situation are the third; for instance, a newly elected Prime Minister, filled with a sense of both duty and potential, will feel a desire to speak to the public and magnanimously express their respect for the previous leader, their humility and their plans for the future – in Jamieson’s words, the situation demands it and the audience expects it (Jamieson 1973). Repetition of these occasions and of the appropriate response over time leads to its own rhetorical genre, exemplified by the ritualistic leader’s conference speech or Prime Minister’s questions in the UK, with past responses to similar situations reinforcing each genre by calcifying the aptness of a certain rhetorical style, structure and technique.

Bitzer’s belief that these repeated, recognisable ‘rhetorical situations’ ‘call forth’ and ‘dictate’ particular verbal responses has been persuasively challenged by Vatz, however, who argues against Bitzer’s underlying argument that orators discover meaning within situations rather than create it themselves (Vatz 1973). Vatz criticises the claim ‘that the nature of the context determines the rhetoric,’ suggesting instead that the conceivable context for each rhetorical situation is almost infinite, and the orator’s role is to provide an initial ‘linguistic depiction’ of the situation, delimiting what they consider to be the relevant elements of context in order to frame their argument. Situations such as the example of the newly elected Prime Minister’s speech may incentivise a particular response, but they are not determinative – indeed, part of an orator’s message may be conveyed by stepping outside the particular speech genre that is expected of them. For instance, Jeremy Corbyn, as leader of the Labour Party, initially rejected the adversarial rhetorical genre prevalent during Prime Minister’s Questions by employing a tone of ‘seriousness and sincerity,’ adopting the words of constituents ‘Marie’ and ‘Steven’ within his questions (Guardian, 16 September 2015). In this way, he sought to reshape rhetorical conventions as part of a wider attempt to challenge norms within Westminster politics. However, the limited results of this ‘kinder, gentler’ style, which Waddle shows made ‘no significant difference’ to whether his questions were answered in more detail, suggests the correct conceptual approach is a synthesis of Bitzer and Vatzs’ perspectives; rhetorical situations do not determine responses, but they do incentivise certain types of verbal response – in the case of PMQs, an adversarial style – and are therefore formative to an extent (Waddle 2018).

In Bitzer’s account, the verbal response which rhetorical situations call forth is either more or less clear to an orator depending on how highly ‘structured’ the context is, referring to the extent of the agreement between audience and orator on what constitutes the context before the orator’s initial linguistic depiction. A travelling preacher speaks in loosely structured rhetorical situations because they are looking for audience and constraints and, when they do find an audience, are less clearly constrained by a defined genre than, for instance, Jeremy Corbyn at Prime Minister’s Questions, where a mutually understood genre provides the situation with structure. Finlayson shows the importance of structure to rhetorical situations for signifying expectations to the audience and speaker, locating both parties within the same metaphorical ballpark of shared understandings and providing a set of resources to draw from. For instance, within a rhetorical genre, orators can demonstrate their credibility as a speaker by repeating time-honoured tropes and techniques, showing deference to tradition. Through his study of Conservative party leaders’ conference speeches since 1900, Finlayson (2015) demonstrates that highly structured situations provide a uniform endoxa from which orators can draw to establish authority and build enthymemes, Aristotle’s concept of shortened syllogistic arguments based on endoxa. We can see an example of this in Cameron’s 2005 conference speech which made an argument for school streaming:

“Labour’s idea of compassion is to put every child in the same class in the same school, and call it equality and inclusion, but I say that’s not compassion; it’s heartless; it’s gutless.”

Cameron had identified two conflicting premises widely shared by his audience: that ‘individuals should be treated as equals,’ and that ‘we should accept individual differences, and adjust our institutions to them’, deciding to appeal to the latter rather than the former. Given that it is important to adjust for differences, and that some children have exceptional ability, while others have special needs, education should provide different streams of schooling. By emphasising the endoxa he needed, Cameron’s rhetoric thus built upon a value shared within his audience in his particular argument.

____

Changes to the rhetorical situation

The contexts in which political rhetoric in Britain takes place have changed significantly during the late 20th and early 21st century (Dahlgren 2005, Bennett & Iyengar 2008, McNair 2011). In this section I flesh out this argument, using the concept of structure in rhetorical situations to argue that political rhetoric in 21st century Britain takes place in what I term ‘de-structured’ rhetorical situations, which lack the traditional indicators of context present in highly structured situations. To demonstrate this, I compare political rhetoric during the 1945 election with three 21st century elections, drawing on studies that have examined reports of campaign meetings and broadcasts.

The 1945 election, compared to 21st century standards, saw a high amount of interactive public rhetorical performance (Clarke et al. 2018). Its label as the ‘radio election’ conceals the varied environments in which the public would interact with politics, attending political meetings ‘outside pubs; at the local works; on greens, squares, and market-places…’ and recognising attendance as a social norm (Clarke et al. 2018: 226). These events were public, often without constraints on who could attend, meaning that the atmosphere and expectations of the audience could be unpredictable – one report from Mass Observation described a meeting in Watford as ‘literally up-roarious,’ the crowd heckling any perceived ‘misrepresentation or sneering remark’ (Clarke et al. 2018: 228). These events were clearly physical ordeals for politicians who were expected to show the common touch and humility, with listeners tending to respect speakers who were logical and willing to interact with audiences, as we can see through this report from a member of the public:

“Very authentic – Beveridge and a rising party and very reasonable. Absence of mudslinging … Good question intelligibly answered and admission of difficulty. Penrose a good debating speaker” (Clarke et al. 2018: 230).

The local nature of these campaign events, where politicians direct rhetoric specifically to the community they speak to, provides audiences and orators with an initial shared sense of context. Standing on a soapbox surveying their audience, skilful speakers can sense the mood of the audience and develop an appropriate response. The open nature of audience participation is beneficial for orators; as Parks (1982) suggests, if the audience is something to be ‘adjusted to or accommodated to’, as our synthesis of Bitzer and Vatz suggests, then direct and dialogic relations between audience and speaker, in which orators are exposed to the heckling or cheering of audiences, guides orators in making these adjustments. Building on Goffman’s work on social encounters, Clarke et al. demonstrate that the resources in these situations – local etiquette, community, values – are responded to by skilful orators, who demonstrate a capacity to adapt their performances to the constraints of different local contexts (Clarke et al. 2018: 223).

These soapbox stages are also structured through physical dynamics, such as the orator’s location in front of and sometimes above audiences, or the anticipatory waiting before the speech begins. As Atkinson (1984) suggests, such physical dynamics can confer authority onto the speaker and create a sense of unity within audiences. Referencing Martin Luther King’s 1963 ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, Atkinson’s emphasis on the importance of physical space and crowd reaction reflects Bitzer’s suggestions for how highly structured situations construct a shared sense of context, in which audiences must be together rather than scattered.

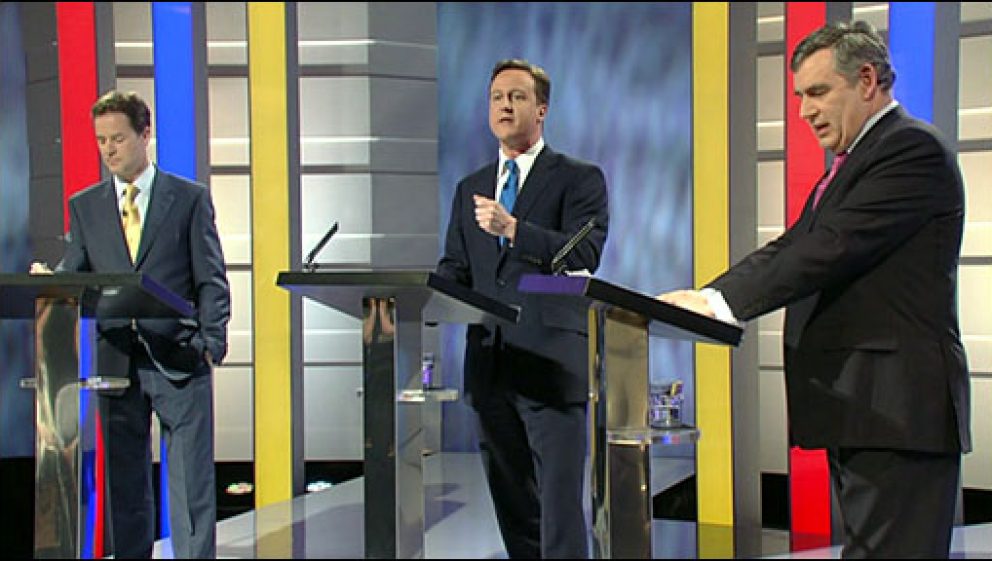

Significant changes to the ‘soapbox’ rhetorical culture began in the late 1950s. Participation in local campaign events, common in 1945, started to decline, and British Election Study researchers stopped studying them after 1992. Rhetorical communication became less candid as political parties increasingly controlled where and how political rhetoric occurred, replacing public meetings with media-oriented conferences and television broadcasts (Rosenbaum 1997). The television interview became established during the 1960s, though by the early 1990s some commentators believed the ease with which politicians tended to handle themselves and deflect questions meant the televised interview had become ‘neutralized’ as a form of journalism (Harris 1991, Bull & Mayer 1993). New hybrid forms of political interview that blend talk show presentational styles with political content subsequently emerged, representing a shift towards ‘infotainment’ or the blurring of boundaries between news and entertainment during the 1990s (see Franklin 1997). Televised debates between party leaders were introduced in 2010 to supplement the political interview, characterised by brief responses to questions posed by journalists who acted as mediators between the public and the politicians (Cowley & Kavanagh 2010). Unlike public meetings in 1945, where politicians engaged directly with heckling or cheering audiences, interaction became tightly controlled and follow up questions banned. Rather than speaking at length, politicians appeared to deliver pre-prepared responses, creating a perception of stage-management from viewers who considered them insulated and sterile, ‘over-rehearsed both in content and technique’ (Clarke et al. 2018). Characterising these differences, Rosenbaum suggests that rhetoric had progressed ‘from soapbox to soundbite’ (Rosenbaum 1997).

Within these situations, the rhetorical context is less clear because the relationship between speaker and audience is more distant. This makes it harder for orators to adjust their performance to audience responses. During leaders’ debates, this relationship is mediated both by a journalist asking questions and through the editorial selection of reaction shots from the studio audience – instructed not to applaud or boo during the 2010 debates – which has been shown through psychological studies to influence how television viewers judge rhetorical performances (Nabi & Hendriks 2003). Without the interactive element, rhetoric lacks a participatory quality, with television audiences feeling like ‘late-coming spectators’, distanced from the event and with more difficulty in comparing performers (Clarke et al. 2018: 251). The elements of audience and context are less tightly tied together than in Bitzer’s ideal type of highly structured situations.

Televised consumption of rhetoric means that viewers are also distanced from other viewers, contributing to a fragmentation of the ‘audience’ itself as a coherent collective. By contrast to the soapbox culture, modern television viewers consume rhetoric in a domestic context; they are isolated from each other; they have other channels competing for their attention. Through a study of television audiences in the United States, Webster has demonstrated that audience fragmentation is ‘more advanced than is generally recognized,’ as television viewership has spread out across a far wider range of emerging cable channels since the 1970s (Webster 2005). In a modern comparative context, the fragmentation of television audiences in 2016 in the UK has been shown to be higher than in the United States, with viewers dispersed more widely across different news sources (Fletcher & Nielsen 2017). Interpreting these changes, Finlayson (2019) has suggested that the concept of audience as a collective body of citizens has given way to an understanding of viewers as a collection of individuals, a set of consumers who ‘weigh up each party’s offer,’ rather than as a cohesive group. Overall, traditional markers of context such as audience reaction and distinctions between genres have become far less clear in the age of televised rhetoric.

____

Rhetorical performances of leadership

This section connects my de-structuring thesis to political leadership. I first draw from social identity theories of leadership to suggest that successful leadership, like successful rhetoric, requires adaptability to the dynamics of the group, before showing how the changing foundations of rhetoric impact how leaders perform these adaptations.

Modern literature on political leadership can be separated into two broad strands (Haslam, Reicher & Platow 2011). The first builds on Weber’s concept of ‘charismatic leadership,’ in which the leader employs their exceptional inborn gift to inspire, persuade and influence in order to motivate followers and overcome challenging circumstances (Weber 1919). More recent iterations of this tradition can be seen in the work of Burns and Bass on the concept of ‘transformational leadership,’ referring to the top-down capacity that exceptional leaders have to transform followers’ abilities and ideals (Burns 1977, Bass 1998).

The second draws from social psychology, suggesting that successful leadership depends not on a leader’s ability to inspire and dominate from above, but to lead from within the group by constructing an identity suited to their followers particular social identity, the common values, beliefs and even styles of dress – in rhetorical terms, the endoxa that permeates their followers (Fiedler 1967, Tajfel & Turner 1979). This conceptualises leadership as a two-way, ‘exchange’ based relationship, in which leaders are shaped by their followers but also shape them, emphasising the particular elements of endoxa which suit their message. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis, Boris Johnson employed the metaphors of armed conflict on March 17 2020, vowing to ‘win the fight’ and ‘beat the enemy.’ This language draws upon endoxa of the ‘Blitz spirit’ and wartime solidarity in the national consciousness – had the government policy been to avoid lockdown, then Johnson may have drawn from different traditions of individual liberty and ‘English freedoms’ (Guardian, 17 March 2020).

This strand rejects the claim that a universal set of leadership qualities exists, instead suggesting that leadership is a ‘process of managing social identity’ and that the traits and qualities of a suitable leader vary depending on the culture and values of the group. The best leader is a different one for each group. Leaders are expected to appear in touch, both a member and a leader of the group, both ‘for the people’ and ‘of the people.’ In this way, democratic leadership exists in tension between the ideal of popular sovereignty represented by the ‘of the people’ leader, and the first strand of leadership which calls for exceptional and superior individual abilities – successful leadership will present itself as the former whilst also possessing the latter, a balance labelled as the ‘art of artless persuasion’ (Kane & Patapan 2012).

Traditionally, highly structured rhetorical situations provided an important setting for politicians to perform this balance. As previously discussed, the tight connection between audience, speaker and context provides resources for leaders to draw from and respond to such as genre, tradition and group dynamics. Speakers standing in front of an audience sometimes will just know what to say. However, as rhetorical situations have become de-structured, this performance has become more difficult. As Alexander (2004) argues from a sociological perspective, political leadership in contemporary societies requires making appeals to far more diverse, fragmented audiences where culture, values and modes of thinking may not be shared at even a basic level.

In this environment, endoxa is fractured and the process of forming arguments from shared foundations, thus self-presenting as someone with the ‘common touch’, becomes more challenging. Political rhetoric within these de-structured situations tends towards increasingly constructed and contrived performances of the ‘common touch,’ often with no relationship to the leader’s ‘authentic self’ (Enli 2015).

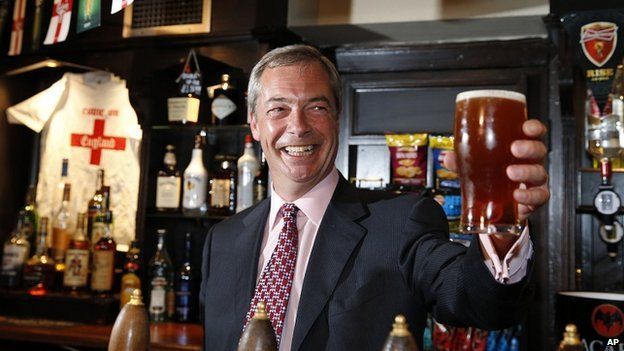

Rather than truly developing the traits audiences value, the decreasingly candid nature of political performance and the growing mediation during moments of political rhetoric means leaders have greater space for preparing their projections of self and constructing a certain ethos for public appearances. The studied shambles of Boris Johnson’s appearance, or the pub-going, cigar-and-pint-image of Nigel Farage act as a reinforcement of the politics they aim to represent, Farage metaphorically embodying the man on the Clapham omnibus, or Boris Johnson representing politics as ‘muddling through’ (Finlayson 2016). In this way, leaders are making increasingly contrived attempts to draw from endoxa during their rhetorical performances. Recognition of this is partly why rhetorical studies in the UK have, since 2000, become increasingly tied into analyses of leadership performativity, referring to the broader ways political leaders project their ‘mediated persona’ through communicative pathways (Corner 2000, Gaffney 2013).

One technique modern leaders have used for projecting this persona is through the adoption of new rhetorical ‘frames’ (Drake & Higgins 2012). A frame’s purpose is to contextualise speech within a particular communicative code by employing certain language and gestures that ‘frame’ rhetoric. In de-structured rhetorical situations, this provides audiences and speaker with a mutual understanding as to what sort of rhetorical performance will follow. In the UK, the most prominent is the ‘celebrity frame,’ documented in the early 2000s by Street and Marsh, referring to the increasing rhetorical performance of informality and ordinariness within politics (Street 2004, Marsh et al. 2010). The term ‘celebrity’ refers not to the world of Hollywood glamour, but the more grounded form of ‘everyday celebrity’ that reflects the ‘local person made good’, such as stars of the X-Factor (Wood 2016). The celebrity frame appropriates an informal code of gesture and speech, allowing politicians to reimagine the boundaries of political rhetoric and to create new types of connection with audiences.

This was particularly prominent during the 2010 party leaders’ debates: Cameron’s performances conveyed informality through repetition of personal pronouns and use of conversational phraseology such as ‘I mean… I do think,’ and his frequent references to the government as a ‘team’, rather than the state (Drake & Higgins 2012). Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg gained attention by sharing details of his sex life in a GQ interview beforehand with an intimacy and informality that shocked because it sat outside the genre of traditional political speech (Parry & Richardson 2011). By speaking like this, politicians implicitly legitimise new forms of political representation by participating in the early stages of a growing rhetorical tradition and changing the ‘sort of thing’ that audiences recognise as political speech (Finlayson 2018). Taking Bitzer’s conception of rhetorical genres as resources, the frame of celebrity legitimates a new set of resources for leaders to project their character by performing a ‘closeness’ that compensates for their mediated interactions with the public (Street, 2004). Leaders thus adjust their rhetorical approach to suit the new context.

Yet, this framing device creates a new set of communicative problems. By shifting the representative link towards intimate informality, leaders find it harder to communicate the difficult, divisive decisions which are central to politics, starkly resurrecting the dilemma of ‘dirty hands.’ The role of political leadership means that making hard, painful choices is everyday work, and politics functions when good people take the necessary decisions to win power and enact it, even when these decisions burden them with guilt (Weber 1919). Walzer describes this as the politician who has fiercely expressed their condemnation of torture yet finds themselves in a position where they ‘must’ use it to locate a ticking bomb (Walzer 1973). The ‘good’ politician here is recognisable by their dirty hands – they are moral enough to feel immense guilt, yet not too moral to avoid these necessary choices. The frame of celebrity, though it may enable affective relationships of intimacy with audiences, does not do for expressing the weight on the politician’s shoulders, the gravity of their decisions, and the occasional necessity of breaking their own moral code. In the business of politics, deceit and lying are, as Jay (1999) terms it, part of a pragmatic discourse, sometimes required out of party solidarity. The conflicting personas of the ordinary, intimate celebrity politician and the tragic figures discussed by Walzer and Weber find a real-time clash in broadcast interviews, where the politician who shifts to the personal frame of reference to answer questions can discover that deceiving and lying for the ‘party line’ are less tolerable when presented as part of an authentic, personal self (Watts 1997).

A further difficulty facing the celebrity frame is the construction of convincing performances of authenticity – how can politicians persuade us they are genuine? As Enli (2015) suggests, political authenticity takes the form of performance, yet when the performative element becomes transparent to audiences, a sense of inauthenticity is created, as exemplified by the use of anecdotes in political argument. Indeed, since 1980, the anecdote has steadily overtaken the quotation as a reference in party leaders’ conference speeches, reflecting a broader trend towards appeals to ordinariness and everyday experience (Atkins & Finlayson 2014). The anecdote works as a ‘synecdoche,’ a part meant to represent the whole and convey ethos – the stories a leader tells about themselves express their character. Yet as this tactic for constructing an identity becomes obvious to audiences, it must evolve. David Cameron’s reference to a ‘40-year-old black man’ during the 2010 election debates was noted in the media not only for its transparent strategic overtones, but also for its inauthenticity, for example (the man was 51, among other errors) (Atkins 2013).

However, speaking directly to audiences can be harder than it seems.

Considering these challenges to the celebrity frame, we can see the need for leaders to manage a sense of social identity within groups. Changes to the rhetorical situation have destabilised the important rhetorical basis for forming these connections with groups, however. More recently, leaders have turned to more direct modes of communication in attempts to perform ‘closeness’ to audiences and avoid the problems of the celebrity frame – recent moves from Downing Street favouring direct self-publication through Twitter rather than broadcast media reflect this dissatisfaction (Guardian, 3 February 2020).

As an online rhetorical medium, Twitter perhaps represents the ideal type of a de-structured rhetorical situation: word use is restricted and the audience consists of potentially any platform user because of the ‘retweet’ function, meaning rhetorical situations are often unconstrained by mutual understandings of genre or context. From a media ecology perspective, which focuses on the aspects of communication technology that shape how it is consumed, Brian Ott argues that Twitter’s character limit demands simplicity, which undermines complex rhetorical discussion, and that it requires minimal effort, which inhibits reflexivity and promotes emotionally charged content (Ott 2016, Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, 2013). In response to these constraints, leaders’ political use of Twitter has moved away from a professionalised style to a ‘more amateurish yet authentic style’ that counteracts the rhetoric of expertise (Enli 2017). Rather than trying to seem professional, some play along with the informal Twitter style. We see how, presented with this new ‘Twittersphere’ rhetorical context, the rhetorical toolkit that leaders use to connect with audiences and manage social identity has, in turn, changed. Across these new and distinct platforms, leaders demonstrate a ‘performative flexibility’, following the demands and dilemmas of democratic leadership in increasingly de-structured rhetorical situations (Craig, 2016).

____

Conclusion

Studying 21st century Britain cannot give a universal explanation of the relationship between political rhetoric and leadership, but it does illuminate points of connection. Central to both is the requirement for adaptability – adjusting rhetoric to fit the situation and adjusting performances of leadership traits to fit the group. Rhetoric is an important tool of leadership, enabling politicians to forge relationships with groups by drawing from the endoxa which unifies them. I have also made an argument about the consequences of recent changes to the rhetorical situation in which this occurs. If leadership depends on rhetorical performances, and rhetoric depends on context and situation, then contemporary changes to those contexts and situations where rhetoric is performed threaten the basis on which leadership is built.

Some of the changes to these conditions, in particular the ‘de-structuring’ of the rhetorical situation, create problems for political leaders. Under these conditions, relationships between audience and leader become more distanced; the capacity for rhetoric to unite audiences through their common endoxa is diminished, as consumption of rhetoric is less of a shared experience. The authoritative position of political leadership is diminished too, becoming one voice sharing the online stage with many. Politicians are left grappling for authority and authenticity, competing with younger, more adept media performers and self-publishers within this new landscape.

Without shared, physical, public moments for rhetorical performances, the relationship between leader and the public is more strained and less able to communicate the tensions that political decision-making inevitably creates. Without these points of connection, broad appeals to an audience as a collective group may become less plausible, incentivising more narrow political appeals and a less unifying form of politics. It is unclear whether leaders will be able to ‘frame’ their rhetoric to forge authentic and authoritative relationships with the public under these conditions. Further research is needed into how leaders might manage social identity within the modern media climate, and whether the connections they form are strong enough to survive politics.